By Peter Dickson

Other sections of Peter Dickson's article appear

at: |

... the pen-keepers in Jamaica are generally found to be, if not the most opulent, at least the most independent, of those who cultivate the soil. Their capitals indeed are not so large as those possessed of sugar-plantations; but then their risks are few, and their losses, except in buildings and provision-grounds, in consequence of storms, are very trifling ... (Note85)

Note85: William. Beckford: A Descriptive Account of the Island of Jamaica, Vol. 2.

At the coves, it was a combination of interests– sugar and rum, cattle and the wharf trade - which offered the best chance of keeping Dickson's enterprise afloat and as free from creditors as possible. It was the very strategy adopted on a larger scale by his father's executor, Donald Malcolm, whose success in business had depended upon several mercantile partnerships and cattle pens in Hanover and St. Elizabeth alongside his sugar work at Alexandria. (Note86)

Note86: Jamaica Almanac, 1811. See also National Archives, London: PCC will of Donald Malcolm.

On an island which relied so heavily on outside finance and the import of made goods and materials to sustain its economy in a tortuous network of bonds, bills and promissory notes, trade passing through Dickson's wharf was an essential source of more ready money; so too was labour on other estates, to whom the Davis Cove gangs could be hired at time of need or 'ticketed" to travel Hanover and its neighbouring parishes for jobbing work.

Ready money, though, was not necessarily immediate cash; "produce at a reasonable price", which could be shifted on at a profit, was accepted as often as unexceptionable bonds or bills of exchange for goods, property and labour. Only a few traders, perhaps mindful of planters intoxicated in advances (Note87) of credit, offered goods exclusively "cheap for cash".

Note87: Neill Malcolm to George Malcolm, 29th August 1801.

PayPal - safe and secure |

|

If you value the information

posted here, |

It was diversity that allowed Dickson to balance accounts with an independence that avoided an over-reliance on borrowed money for the riskier but potentially more profitable business of sugar. He certainly laid an eye to the future for the plantation and the wharf business were carefully reckoned as separate accounts; however, whether the Cousins Cove plantation was a wise speculation at this time remained to be seen.

Writing to Donald Malcolm at Lucea ten years earlier, and in low spirits about particular affairs, brother Neill had been:

... sorry to observe of all my estates that N[ew] Paradise and Blenheim turn out the worst; with the last estate I continue from year to year to be egregiously disappointed in my expectations and tired at looking how little it has reduced its original cost in the best years that planters will probably ever see, and with all the great character of that estate and your reluctancy to part with it, I certainly took a thorn out of your foot and put in [sic] into my own when I took to it ... it has hitherto proved a pickpocket". (Note88)

Note88: Neill Malcolm to Donald Malcolm, 29th July 1801.

|

|

|

Abingdon great house, Jamaica. |

At around the same time, Lady Nugent, wife of Governor Nugent and an outsider to the business had observed in her diary.

… It is wonderful the immense sums of money realised by sugar in this country, and yet all the estates are in debt … I would not have a sugar estate for the world! (Note89)

Note89: Maria Nugent Journal, 24th Feb. 1802

On the real wealth of sugar proprietors she may have been seduced by the system of boasting common to planters ... (Note90) and overlooked the point that heavily mortgaged owners with interest on loans, commissions on trade and expenses to cover habitually took on continual credit and only realised a return upon the sale of shipments by their agents.

However, she was too astute and too close to her husband's affairs to be unaware of the principal concerns which constantly exercised the minds of planters, merchants and the civil authorities: events which might threaten "the tranquillity of the country" (Note91) or the balance of public and private accounts - weather, war and civil unrest; the co-incidence of any two could prove ruinous.

Note90: Neill Malcolm to George Malcolm, 29th July 1801.

Note91: A phrase used time and again in official reports to London

|

|

|

Jamaica100 CP sugar pot, Jamaica |

1780 had ushered in a decade of violent storms which blasted different parts of the island on different occasions, one of the worst being the October hurricane of that year, a dreadful calamity which befel the western-most parishes. Savanna-la-Mar, on the south coast, was all but destroyed. Perhaps on business or on a personal visit to his cousin James Dickson who, three years earlier, had had "the honour of being ... appointed master at Manning's Free School” (Note92), John Dickson was in the locality at the time and joined with the remaining destroyed inhabitants of the place in subscribing a letter to the governor in a plea for help.

Note92: Cornwall Chronicle & General Advertiser, 1777.

... that morning the wind became more violent than usual, with a most terrible swell of the sea, which, by afternoon, encreased to such a degree, that it has not left the wreck of six houses on both the Bay & Savanna, not less than 300 people of all colours were drowned, or buried in the ruins - such terrible havock was never seen in the memory of the oldest person here, nor can words, or writing, convey an idea suitable to the dismal scene ... our accounts from the country, and also from Hanover, are equally melancholy: scarce a house standing on any estate, and all the provisions destroyed ... (Note93)

Note93: Letter to Governor Dalling, 3rd Oct: CO137/79, pp 15-16. Pages 15-44, letters and newspaper reports about events and the organisation of relief.

Further north, in Hanover, John Campbell, although "confined at home since that fatal day at Salt Spring, reported an equally miserable situation (Note94) in a succinct letter making similar representations to the governor's secretary from survivors there. By this John Campbell's later estimation, one quarter of the value of property in the parish was lost and would take many years to make up. (Note95) In St. James, John Palmer, Custos of that parish, presented yet another plea from Montego Bay.

Note94: Letter to John Clement, 10th Oct: CO137/79, p. 17.

Note95: Letter to John Clement, 15th Oct: CO137/79.

With provision grounds uprooted and an ensuing dread of famine stirring alarm, the response from unaffected merchants and government alike was remarkably rapid at a time when communications relied solely on physical stamina - both animal and human. Within two weeks an immediate £10,000 was raised by subscription in Kingston (Note96) and small convoys, under naval escort, were ordered to Lucea and Savanna-la-Mar with relief in the way of provisions, shoes, coats and a small detachment of troops, should they be needed; arrangement were also made for two shiploads of rice to be bought in America (from Charleston and Savannah, both still under loyalist control) and a packet was told off to sail for England, carrying letters from distressed merchants and planters to their suppliers, agents and, above all, their creditors.

Note96: N.A. CO137/79. The Governor himself started the fund with £2,000.

Ten months later there arrived a £20,000 donation from Parliament to be parcelled out to planters who could not or did not entertain the idea of engaging additional credit elsewhere. Applicants in Hanover were to apply to John Campbell at Salt Spring and Peter Campbell at Fish River, both on a committee of nine gentlemen of the county nominated by the Jamaica Assembly. (Note97)

Note97: Resolution of the House of Assembly, reported in the Cornwall Chronicle, 25th August 1781. Committee: George Goodin, Peter Campbell, William Dunlop, John Wedderburn, Charles Bernard Junior, William Beckford, John Campbell, Richard Watt and Robert Mure.

With crops destroyed on so many plantations, little or no income could be expected for a while, yet some planters had neither the inclination nor the wherewithal to make good immediately, even with the prospect of Parliamentary money. Nine months on, John Samuels, still coming to terms with the death of three family members on the day, as well as the damage to his estate, felt obliged to offer a lease of up to seven years on "fifteen to twenty seasoned field negroes" (Note98) who could not be usefully employed by him at Cousins Cove nor by William Samuels at Negril Spotts estate further south, in Westmoreland.

Note98: Cornwall Chronicle: July 25th 1781.

Following such sudden destruction, a certain wariness about the immediate future may have taken hold for even the occasion of moderately heavy weather could spoil a crop and the cane fields for more than one season, as Simon Taylor detailed eight years later.

|

|

|

Slaves per ship Iris, Jamaica |

we had no Storms nor Floods last year, and matters were going on very smoothly and prosperously until the 22nd of this month, when we had the severest and heaviest flood, that we have had for these 23 years, indeed infinitely higher than in any of the Hurricanes which has done the Estate in the River a very great deal of damage indeed, by carrying of the Trash intirely of some pieces, laying it on other, tearing up some Canes by the Roots, washing out the young Plants, and laying trash on some of them, indeed had it happened earlier in the Crop, it would have intirely destroyed it, but as it is it will do this one a great deal of Injury, and I am afraid hurt the next one ... (Note99)

Note99: Institute of Commonwealth Studies, Simon Taylor Archive (Vanneck-Arc/3A/1788/item 10).

A storm at the East of the island on 2nd August 1781, which scattered and cast up on shore so many of the fleet assembling off Port Royal for the convoy to Britain, caused sufficient havoc to warrant the prompt dispatch of yet another naval packet to carry yet more bad news to merchants and creditors in Britain. Duncan Campbell's ship, Orange Bay, driven on to the rocks below the Twelve Apostles battery, was at first "thought totally lost ... but contrary to expectation, was ... got off, by the care and activity of John Henderson Esq. and most of the cargo ... saved". (Note100)

Note 100: Cornwall Chronicle, 18th August 1781.

Campbell and Henderson were fortunate; of 83 topsail vessels which either foundered or were grounded only 43 were recovered in various states of repair and later able to make their way westward or return to island trade; of the smaller inshore craft some 120 were reckoned destroyed. All in all, rather fewer than the previous year’s total of 136 ships (Note101) that had sailed from Jamaica London alone would return goods to the City market.

Note 101: Cornwall Chronicle, 8th December 1781: From 25 March 1780 to 25 March 1781 136 ships arrived at London with 49,158 hogsheads of sugar and 12,014 puncheons of rum.

At sea, however, misfortunes attendant on the weather were only one hazard to contend with in the midst of national hostilities. By 1777, within a year of American naval activity in the Caribbean and its Atlantic approaches, Provincial privateers had already accounted for losses amongst West India merchantmen amounting to some £1,000,000. (Note102)

Note102: Cornwall Chronicle, April 1777: A report completed in December 1776 by Governor George Johnstone in ... ? and a Captain Laurel.

The "Africa trade" was likewise affected, with captured slaves being discreetly sold off at Martinique, other French islands or taken home; the losses here were reckoned at just under £190,000. Although these figures were presented at the time as evidence of the effectiveness of the Earl of Sandwich's naval policy, they represented grievous losses to merchants and ship owners. If Edmund Parkinson (of Parkinson & Hill at Montego Bay) and other resident merchants engaged directly in the Africa trade, such news so early in the war perhaps persuaded them that it should be left to those who were prepared to take the risks and who could afford to take them - London factors with longer pockets who could hedge their Jamaican commitments with less risky business elsewhere. Parkinson parted not only with the wharf and buildings at Davis's Cove but also put up for sale the snow, Fanny, only four years old, complete with all her Guinea materials, lying at Lucea. (Note103) He would return to the Africa trade in the next decade, after the war.

Note103: Cornwall Chronicle, advertisement February, March 1777.

Upon the later arrival of French and Spanish men- o-war and privateers in the area, the Lucea station was a busy one, given the proximity of Cuba and St. Domingue as close havens for enemy vessels "destined for depredations upon the coast of this island, on shore, as well as by sea". (Note104)

Note104: Cornwall Chronicle, 1 September, 1781.

The Spanish introduced their Mediterranean practice of using oared galleys for a fast approach and withdrawal from shore, although they were no match for armed merchantmen with crews answerable in the open sea nor for any of His Majesty's ships. Protection of that sea to the Windward and Florida passages, the start of the long Atlantic roads eastwards and northwards, was vital to the island's fortunes and, by 1781, the continuing cost of such protection became an additional burden to the island's merchants. For the defence of harbours, the Assembly passed an act for laying a duty on Tonage and applying the same to Forts and Fortifications. (Note105) Off-shore, in a continual round of the capture, loss and re-capture of ships, local initiative and enterprise also played its part alongside the Royal Navy and private vessels with letters of marque.

Note105: Cornwall Chronicle, 8 December 1781: report on the proceedings of the House.

Montego Bay, 15 September 1781

The services of Messrs. Monteath's ... schooner at Green Island …are too recent to need recollection: we wish that the gallant volunteers, who, upon every alarm, and appearance of an enemy, have boldly stepped on board for the defence of the sea coast of this country, may meet the just reward their merit deserves by a general subscription throughout the County of Cornwall, for their encouragement. (Note106)

Note106: Cornwall Chronicle.

|

|

|

Map of Green Island Harbour, Jamaica |

The Monteath schooner's most recent success was particularly welcome as it had captured an armed sloop that was preying on valuable West coast traffic and which, on its own, had cost local trade the loss of twelve ships and 35 Negroes. These ships were local, delivering cargoes to Britain-bound ships secure in the larger harbours, and the loss of experienced negro seamen hit particularly hard; white seamen who survived an encounter and found themselves prisoner may have been habitually exchanged under a flag of truce but negroes were kept by the enemy as slaves. Conversely, captured enemy slaves were employed as free men if they defected, an established practice for over one hundred years in the West Indies (Note107) and one adopted by British commanders in continental America. (Note108)

Note107: Sir Henry Morgan's Voyage to Panama, 1670, Thomas Malthus, London 1683: Thomas Modyford's commission to Henry Morgan [1670] - you are to proclaim …Liberty to all the Slaves that will come in and to such as by any good service may deserve the same ...

Note108: cf. Simon Schama, Rough Crossings, (Britain, The Slaves and the American Revolution), 2005, BBC Books and Hugh Bicheno Rebels and Redcoats, 2003, Harper and Collins.

Crossing the Atlantic, the master of a merchant running ship, impatient to await the assembly of a fleet and who gave up the protection of a convoy, increased the perils of the voyage; some took the chance on urgent business, relying on speed and skill to outrun trouble. John Campbell, on a voyage to Britain from Salt spring in late 1782, was unfortunate to find himself aboard a ship that was captured by an American privateer and taken to New London, Connecticut, where he died early that November. (Note109)109

Note109: W. A. Feurtado: Official and other Personages of Jamaica 1655 to 1790.

Both then and later the risk of sailing without escort was unavoidable by the Royal Mail packets which, fast as they were and on their own, were ever objects of predatory action. However, even lightly armed, they had some teeth, with the right leadership, and were not afraid of action that could be very lively.

Sir, I beg to inform you that on March 10, 1808, at three P.M., Port Mourant W.N.W distant four leagues, Prince Ernest of six guns and 28 men and two passengers, fell in with a French schooner of 10 guns (four of which of large calibre) and upwards of 100 men. We commenced action and continued until six P.M. The first ten minutes was very warm and close, within pistol-shot, when his large guns did great execution among the sails and rigging, and two of my fine fellows and myself were wounded. In the course of the first two hours she attempted twice to board, but was repulsed with great slaughter and the last time, at five P.M. with a discharge from great guns and small arms, she laid me alongside, but my choice little crew were ready to receive them, and they appeared panick-struck with the loss of two of their best men at the helm. When alongside, they hauled off on our larboard beam, and fired a few shot, but without much effect, and at six P.M. ran away to the northward under her square-sail and top gallant-sail not being able to make any sail on her main-mast, it being very much wounded. I have great satisfaction in saying that every Officer, men and boys, have done their duty to their King and country ... (Note110))

Note 110: Royal Gazette of Jamaica: March 1808

It was not unusual to hear of a crew "feted and given handsome cash awards". The successful repulse of hostile action brought rewards which were a measure of the value of shipping to the Island's merchants, whose exchange of legal papers, bills and goods would have been otherwise impossible. Warm words were habitually accompanied by a generous cash bounty which went a long way to encourage crews to show robust determination. Captain Petre and his crew experienced just this from a grateful Mayor of Kingston.

The merchants and other inhabitants of this town have come forward with their usual liberality, to reward the gallant crew of the "Prince Ernest", and it is proposed that the sum of 700 Guineas, which has been raised, shall be appropriated in the following manner, viz. To the Captain, 200 Guineas, Master 100 ditto, Mate 50 ditto, Boatswain, Gunner and Carpenter, each 25 ditto. Each of the crew, 10 ditto. The present was accompanied by a very handsome letter from John Jaques, Esq. Mayor of Kingston, in which the gallant and good conduct of Capt. Petre, his officers and crew, are acknowledged in the warmest of terms. (Note 111)

Note 111: Ibid.

Although generosity on this scale was not unusual it was, nevertheless, still quite astonishing as it may have represented about a quarter of the ship's value in this case. (Note112)

Note 112: In September 1794, RMPB Antelope, England bound out of Falmouth, Jamaica, was captured by a squadron of French frigates; the loss was valued at £2,784. 18s. 6d.

The fear of civil unrest was, until much later, greater than any actual consequence for the established order of affairs. Parish militias, supported when necessary by a reserve of regular troops and a navy well practised in the prompt loading and landing of soldiery, were sufficient to contain any disruption to little more than a local inconvenience. A young Neill Malcolm had written from Hanover in 1760 that:

... this unhappy insurrection of so many of the negroes has kept people in this and the neighbouring parishes so much harras'd doing duty and going out in parties into the woods after them that nothing was observed for some time past, but strickt discipline as martial law directs ... (Note 113

Note 113: Neill Malcolm to Alexander Malcolm of Glennan, 3 Augst 1760.

Sixteen years on, news of events in the American colonies, and the withdrawal of troops from the Lucea garrison as a consequence, prompted an uprising amongst domestic slaves in Hanover and Westmoreland. However, relying on its own manpower, the Militia of Hanover…ordered out on duty; every company in rotation with a party of horse, who relieve every forty eight hours was sufficient to contain the affair and to see that rebel slaves were "brought in from many estates and confined in irons" to await trial. (Note114)

Note 114: Cornwall Chronicle, 19 April, 1777.

Later revolution in France, the subsequent French wars, rebellion on French St. Domingue and a simultaneous uprising by the Trelawny Town Maroons in the last decade of the century only increased fears that a dangerous spirit would undermine strict discipline in Jamaica.

(The Maroons were descendants of earlier-freed or runaway Spanish slaves, some of whom had fought with the English against the Spaniards. In 1738, following the First Maroon War, terms were made with the government under which the Maroons were guaranteed full freedom and liberty and granted land. In return they agreed to help recapture runaway slaves and assist in military operations against local uprisings or foreign invasion. Two Superintendents of Maroon were appointed to live with them to maintain friendly contact. After a second Maroon War in 1795, those who had rebelled eventually arrived in Freetown, Sierra Leone, Africa, via Nova Scotia.)

During the short lived peace with France, which brought a hesitant respite in 1802, the island was crowded with refugees from St. Domingue but the authorities were so alarmed at the possible spread of any revolutionary infection that foreign white persons, and their slaves, were dispatched to New Orleans at government expense.

And war had particular economic consequences for an island so reliant on naval traffic and the sale of its commodities abroad. The West India merchants in London, keen to protect their outlay of advances to clients abroad, could count on influence to raise shipping and insurance charges - and also a little more. A general meeting in September 1781:

... took into consideration the very great increase which has of late years taken place in the advance of monies for duty on sugar amounting, with freight, at present to near 20s. the cwt. Instead of about 7s. which they formerly amounted to; and that when sugars are kept for a market for the benefit of the planters, the interest of this great advance is wholly lost to the merchants, whereby such keeping is greatly discouraged.

Resolved unanimously:- that interest should be charged in the accounts of sales on duties only from one months after the ship's report, until the time the money for the duties is reimbursed. (Note 115)

Note 115: Extracts from the minutes of a general monthly meeting of the West India merchants, 25th September, 1781 [reported Cornwall Chronicle, 8 Dec 1781].

On the other side of the water, across "the dreadful seas", there was a rather different view of the situation, at least in the Western reaches of the island. Particularly irksome to one older, resident planter at the time, and quite likely to many more given that his opinion was aired, was the sense that they had little say in the matter, being subject to the arrogance and self-importance of naval nabobs, a situation which, in their view, was "an evil pregnant with the most fatal consequences to the prosperity of this community". (Note116)

Note 116: Cornwall Chronicle, 17 February 1783.

However, the naval nabobs themselves were not necessarily immune to the twin perils of war and weather. By the end of 1781, following damage and delay to ships Orange Bay and Green Island in the storm at Port Royal, even Duncan Campbell reckoned on a trading loss of some £4,000 for the year and confided to his cousin John at Salt Spring that he no longer felt "a stranger to the want of money". (Note117)

Note 117: Duncan Campbell to John Campbell at Salt Spring, 28 December 1781.

The ever upward spiral of expense for the island's residents was not the only "evil" to put up with for there were other parties at work in London who made a bold attempt to capitalise on one particular fortune of war and to undercut the price of West Indian sugar. In May 1781, an anonymous "Well-Wisher to the Planting Interest" wrote to the printer of the Cornwall Chronicle in Montego Bay enclosing the following extract of a letter recently arrived from an eminent merchant in London who informed him that:

The Sugar-Refiners are using great diligence to obtain permission, by an Act of Parliament, to use prize sugar at a lower duty, and I am sorry to say, that the desire of having sugar cheap, prevails with many of the members, tho all the arguments on behalf of the Sugar Colonies are used, which at other times have had their due weight. (Note 118)

Note 118: Cornwall Chronicle, 18 August 1781.

It came as a relief to Jamaica merchants that this proposal was staved off and they might have been further comforted by other news from London towards the end of the year. A London Price Current at 6th October, 1781 (Note119), printed in island newspapers in December, listed a range of prices that their produce might fetch.

Note 119: Cornwall Chronicle, 22 December 1781.

Coffee, £5 to £6 per cwt. Cotton, 2s 4d. to 2s 7d. per pound

Fustie, £12 to £13 per ton Hides, 18lb. to 22lb. 6 ¼ d.

Logwood, £6 to £10 per ton Piemento, 9 ¼ d. per lb.

Rum, 5s. to 6s. per gallon Sugar, £3 3s. to £3 10s. per cwt.

Tamarinds £2 2s. to £3 3s. per cwt.

With the August fleet so extensively stripped, advance word of expected shortages on the British markets, carried to London by the packet Vigilant, had clearly inflated prices, a cause of probable intoxication for some planters but gloom for others. Those whose cargoes had survived could look forward to a better than expected yield, those whose goods had perished would have await insurance claims protracted by time and distance. Although prices and expenses would level again, the American campaign, overall, had seen a doubling of freight charges for shipping (Note120), costs which, on their own, had, at times, sliced twenty percent off any return.

Note 120: Cornwall Chronicle; 17 February 1783, a letter to the printer from An Old Planter: by 1783 the freight on sugar had risen to 10s. per Cwt. at a time when sugar fetched between 42s. and 52s. per Cwt. on the London market.

At the onset of the French war, after some ten years of the blessings of peace, the island's merchants and planters, knew just what to expect if that engagement were likely to run for any length of time. Neill Malcolm summarised the early consequences after only a year, already complaining in 1794 that:

... the calamities attendant on the War reached us so severely in the West Indies the Charges attending our internal defence and the Necessary Supplies from our plantations nearly double, equally so the expense of Insurance & freight in bringing our produce to a reduced Market, the consumption at home much lessened and the Usual Channels of Exportation checked, to some places totally stopped ... (Note121)

Note 121: Neill Malcolm to *** McTavish of Dunardry

On the other hand, Jamaican trade with America had opened up again, although the matter of unpaid pre-war debts still lingered. Whilst some of the usual channels of commerce were indeed closed off, subsequent events on St. Domingue would soon lead to the absence of its sugar from the markets, a situation which would also allow Jamaican sugar producers a virtual monopoly, for a while at least; and sugar speculation was not the only means to a living, as the more sober planters were already finding out.

There was a bleak terseness to some of the announcements that John Dickson would have read for the first time: notices of negroes just imported, giving little more detail than the gross number of a shipment and a place of origin. In the last fortnight of June 1754, four hundred and eighty six slaves were landed at Kingston alone, of whom a little more than three hundred might have been expected to survive their first few years on the island, commonly called the "seasoning"; having lived through this, they would become the backbone of the island's prosperity. Later, in Hanover, the business in slaves would be brought even closer to home as both William Brown and Donald Malcolm announced new arrivals for sale at Lucea or Montego Bay (Note 122), and no more than anyone else could newcomer Dickson escape the simple fact that most manual labour, skilled as well as unskilled, was African.

Note 122: Among merchants receiving slave ships in the county of Cornwall, 1776-1794 were: William Brown, Lucea; Parkinson & Hill, Montego Bay; Hibberts, Bernards & Montague, Montego Bay; Malcolm & Nevinson, Montego Bay; John Tharp & Alexander Campbell, Martha Brae; John & James Wedderburn, Montego Bay; Thomas Harper, Montego Bay.

Speculation in the Guinea trade, as a means to fund other business, could be tempting but it could also lead to an unintended tangle of commitments. George Malcolm, having to answer a particular proposal made to him in London in 1799, before his return to Jamaica, wisely sought the advice of elder brother Neill who replied:

... you say Mr. Corrie has made an offer to send you five or ten Guineamen ...if you engage deep in that business you cannot calculate on the number of years in which you can return to Britain after winding up the engagements to which such a business may lead, and if you return without sending a proper provision before you to answer all the bills that you may draw on account of such business it is probable you may meet some person ... hostile [who] may insist upon a more rigorous settlement ... (Note123)

Note 123: Neill Malcolm to George Malcolm, 23 March, 1799.

In the event, Malcolm found himself otherwise engaged in setting to rights those estate affairs which had been neglected by overseers; he died in Hanover in 1813.

Equally unfamiliar to Dickson on arrival would have been the presence of convict "servants", sent down for transportation from various assize courts around the kingdom and amongst whom there was also a debilitating attrition rate. Indentured servants, whom he also relied on, and immigrants completed the island's available labour, but were never sufficient for a government anxious to secure:

... the better peopling of the island with White Inhabitants ... to enforce the Cultivation of Lands in the manner which may conduce best to the Security and Defence of that Island ... and for encreasing the Trade and Navigation between that Island, and Great Britain, as well as to and from other Parts of his Majesty's Dominions. (Note124)

Note 124: 1753, Journals of the House of Commons: John Pitt, Bill for the better peopling of the island of Jamaica with white inhabitants.

Various acts, six in all, passed since 1736 for the Introducing and Encouragement of White Settlers, tradesmen and farmers had met with little success. In the eighteen years between 1736 and 1754 only 690 people, singly and as families, had made the passage at Government expense, a cost of £30,000. (Note125)

Note 125: National Archives, CO137/28, pp 175-180.

Merchants who acted as intermediaries would not have complained: an account of costs between 1750 and 1754, submitted to London by Governor Knowles, included £1,400 Jamaica currency, remitted to Messrs. Barclay & Fuller merchants in London to defray the expence of sending out white familys & tradesmen from thence". (Note126).

Note 126: National Archives, CO137/28.

Further official attempts to improve the pattern of settlement were little more effective but until hostilities with the colonies on continental America intervened the servant trade, as a whole, tried to meet business as usual.

Private arrangements could be rather more productive. While some merchants, agents, ship owners and ship masters worked the markets in slaves and convicts, others had been dealing with indentured servants well before Dickson's arrival and continued to do so; some provided for the Americas generally but also for Jamaica in particular; London, 1731: (Note127

Note 127: Ibid.

If there were dispatchers at one end, there were receivers at the other; William Jamieson, merchant in Kingston, put up notices in the Jamaica Courant [1754] to let it be known that, in addition to ‘Dumblain Linnen, Scots sheeting and Scots Kentings for musquitto nets’, he traded "also the indentures of Tradesmen and Labouring Servants". But if Jamaica was an island fastness to which slaves were consigned unwillingly, it was not necessarily much more of a welcoming place for "servants", some of whom often had second thoughts on arrival.

... you say Mr. Corrie has made an offer to send you five or ten Guineamen …if you engage deep in that business you cannot calculate on the number of years in which you can return to Britain after winding up the engagements to which such a business may lead, and if you return without sending a proper provision before you to answer all the bills that you may draw on account of such business it is probable you may meet some person…hostile [who] may insist upon a more rigorous settlement … (Note123)In the event, Malcolm found himself otherwise engaged in setting to rights those estate affairs which had been neglected by overseers; he died in Hanover in 1813.

Equally unfamiliar to Dickson on arrival would have been the presence of convict servants, sent down for transportation from various assize courts around the kingdom and amongst whom there was also a debilitating attrition rate. Indentured servants, whom he also relied on, and immigrants completed the island's available labour, but were never sufficient for a government anxious to secure:

... the better peopling of the island with White Inhabitants ... to enforce the Cultivation of Lands in the manner which may conduce best to the Security and Defence of that Island …and for encreasing the Trade and Navigation between that Island, and Great Britain, as well as to and from other Parts of his Majesty's Dominions. (Note124)

Various acts, six in all, passed since 1736 for the Introducing and Encouragement of White Settlers, tradesmen and farmers had met with little success. In the eighteen years between 1736 and 1754 only 690 people, singly and as families, had made the passage at Government expense, a cost of £30,000. (Note125)

Merchants who acted as intermediaries would not have complained: an account of costs between 1750 and 1754, submitted to London by Governor Knowles, included £1,400 Jamaica currency, "remitted to Messrs. Barclay & Fuller merchants in London to defray the expence of sending out white familys & tradesmen from thence. (Note126)

Further official attempts to improve the pattern of settlement were little more effective, but until hostilities with the colonies on continental America intervened the servant trade, as a whole, tried to meet business as usual.

Private arrangements could be rather more productive. While some merchants, agents, ship owners and ship masters worked the markets in slaves and convicts, others had been dealing with indentured servants well before Dickson's arrival and continued to do so; some provided for the Americas generally but also for Jamaica in particular; London, 1731: (Note127)

If there were dispatchers at one end, there were receivers at the other; William Jamieson, merchant in Kingston, put up notices in the Jamaica Courant [1754] to let it be known that, in addition to Dumblain Linnen, Scots sheeting and Scots Kentings for musquitto nets, he traded also the indentures of Tradesmen and Labouring Servants. But if Jamaica was an island fastness to which slaves were consigned unwillingly, it was not necessarily much more of a welcoming place for servants, some of whom often had second thoughts on arrival.

Run away, in the night, between the 12th and 13th Inst. from the Ship Antelope, John Scott, Master, lying at Montega-Bay; three white indented servants, viz.

One named Patrick Henderson, a Cooper, born in Scotland, a middle-size Fellow, marked with the Small Pox, aged 18 Years, talks broad Scotch.

Another named Thomas Conway, a Sawyer born in Ireland, a middle-size Fellow, talks much on the Irish Accent, aged about 21 Years.

The other named Kames Keating, Indented as a Carpenter, but knows nothing about the Business; born in Ireland, talks very much on the Accent, a little well-set Fellow.

Whoever apprehends the said Servants, so as the said John Scott may have them again at Montega-Bay ... shall receive a Pistole Reward for each, and be paid all Necessary expences. (Note128)

Note 128: Jamaica Courant, 28 June 1754.

Individual arrangements and private schemes were not without hazard and there might well have been many more such runaways to contend with earlier in the century if Sir James Campbell of Auchinbreck's plan had ever been advanced. On the face of it emigrants were to be given passage to Jamaica but, in April 1740, John Campbell, Duke of Argyll, was able to warn and advise his other kinsmen, in a letter to Archibald Campbell of Stonefield, that the true intent of the design was nothing less than to consign unsuspecting hopefuls to the island as slaves. (Note129)

Note 129: NAS, GD14/12: John, Duke of Argyll to Archibald Campbell of Stonefield, letter, 22 March 1740.

For slaves who ran away, escape from the island was improbable if not impossible and survival in the wild proved equally hard, particularly for those who happened upon Maroons, as reported in early April, 1777. (Note130)

Note 130: Cornwall Chronicle, 19th April 1777.

Sunday, a party of Maroons belonging to Trelawny Town, fell in with a number of runaway negroes in Hanover; three of whom they killed, and brought one in, much wounded. Tuesday, the same party went in pursuit of another large body; part of which were lately seen in the mountains; on the back of Colonel Grizell's estate. (Note131)

Note 131: John Grizell was Colonel of the Hanover Foot Militia.

Recapture or surrender was inevitable for most, followed by gaol or the workhouse and labour for the parish until they were reclaimed; any public expense for temporary subsistence would, of course, need to be paid off as would any reward offered. There might have been refuge for some, for a while at least, with John Marksman of the parish of St. Elizabeth, Yeoman, but it could never last, the authorities being ever anxious to discourage any like action. For the scene of villainy carried on …for some considerable time …by harbouring a great number of runaway slaves, (Note132) Marksman was convicted on three indictments in 1781 and sentenced to six months in gaol with an impossible one thousand pound fine to pay; having escaped from the custody of the gaoler, he too became a fugitive, with the considerable sum of one hundred pounds offered for his recapture.

Note 132: Cornwall Chronicle: Royal Proclamation of October 1781.

He was still unaccounted for two years later when one of the late John Dickson's former carpenters, Sampson, together with young mason Peter, found their new employment with William Hylton, a former acquaintance of Dickson, not to their liking. They were presumed to have taken off from his Delve estate in Westmoreland (Note133), to more familiar ground, lurking about the upper part of Hanover. (Note134)

Note 133: Owner, William Hylton, known to Dickson before 1780.

Note 134: Cornwall Chronicle: a notice dated 14 May 1783.

But, if an official, systemic and perhaps general reaction towards the like of Marksman's doings was to be wholly expected, the unexpected also came to light in individual cases.

June 17 1787

This day sailed from Savanna-la-Mar the sloop the Cygnet .. with whom went a passenger, a Mulatto woman named Jenny Campbell; the tale of whose sufferings has for a long time engaged the attention of the public in this quarter. She was a few days ago brought to trial by her master and mistress, for having struck the latter about six years ago, for having robbed her of some trinkets, and for having fled from her prison. On hearing the evidence, a humane jury released the woman from her apprehensions, by banishing her from her country, her friends and children. Several gentlemen of respectability, in the parishes of Westmoreland and Hanover immediately subscribed to purchasing her freedom, which was done; her passage was paid for, a small sum was given her for her immediate support and letters sent to secure her a reception suitable to her station. A most unequivocal proof of their sense of the treatment she had met with ... (Note135)

Note 135: Cornwall Chronicle, June 1787.

Of Dickson's slaves at Davis Cove Wharf in 1817 all but two of the men were African (Note136), mainly in their forties and fifties which suggests that they had arrived around two decades before.

Note 136: National Archives, T 71/190: 1817 return of slaves for Davis Cove.

However, most of the women there were Creole, and Jamaica-born too was a majority of the Cousins Cove plantation slaves; altogether, they were a mere fraction of over 22,000 working in the parish at the time. On the plantation's return of slaves considered as most permanently settled, worked or employed (Note137) - the number of slaves being recorded annually and each proprietor taxed accordingly - the Africans noted were again, for the most part, in their thirties, forties and fifties; the youngest was 27 years old, the oldest was sixty.

Note 137: National Archives, T 71/190: 1817 return of slaves for Cousins Cove.

All of the slaves were also baptised into the Church of England, a practice widespread on many Hanover estates between 1814 and 1817 (Note138), following a request from the Governor's office to the parish rectors.

Note 138: National Archives, CO 137/144 return of slave baptisms in Hanover Parish 1814-1817.

It was an effort either to promote the religion, decency, and good order ... among the negroes (Note139) which Maria Nugent had advocated some years earlier or to pre-empt the activities of non-conformist missionaries, wholly against slavery, who were regarded with certain suspicion by some proprietors. On two occasions, the one at Cousins Cove where the plantation slaves were housed and had their provision grounds and the other at Davis's Cove, slaves belonging to neighbouring friends and proprietors, not all of whom were white white, joined in the mass baptisms. The new surnames taken were, understandably, mostly Crooks and Dickson although there was a sprinkling of others - Brown, Campbell, Malcolm, Fraser and White; Christian names followed a similar pattern although Abba, Ammie - Jaba and Ebin still looked back to an African past.

Note 139: Maria Nugent Journal, 8 April 1802.

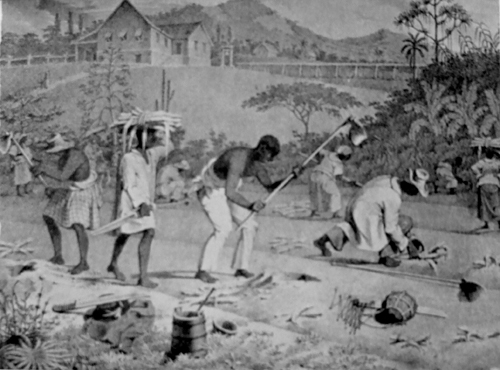

While some had skilled trades as seamstresses, coopers, masons, carpenters and smiths, others were equally skilled in the care of livestock, the growing of canes and the making of sugar and of rum. Apart from domestic servants and trades people, field cooks and water carriers counted for a few more in the number of an estate's slaves but the majority were field hands, including children, for whom the crop time was especially hard.

The smallest children are employed in the field, weeding and picking the canes; for which purpose they are taken from their mothers at a very early age. Women with child work in the fields till the last 6 weeks, and are at work again in a fortnight after their confinement. Three weeks in very particular cases are allowed ... (Note140)

Note 140: Maria Nugent Journal, 24 Feb. 1802.

Saturday and Sunday were allowed them to work in their own gardens and raise provisions for themselves (Note141) to supplement the imported, salted herrings and other victuals supplied by their owners when home grown food was not in crop.

Note 141: Ibid.

Sunday was also market day and a social occasion when surplus produce from the provision grounds, as well as other items made, could be bartered at market or sold for cash. Although available for many years, herring seems to have had a relatively patchy introduction at some estates; George Malcolm on his return to the island in 1800, wrote that he never saw the use of them but now they must be got (Note142) (from Messrs. Stirling & Gordon of Glasgow, the Malcolm agents), but salted herring was not always popular.

Note 142: George Malcolm to Neill Malcolm, 15 Oct. 1800.

As imported supplies were also costly, Dugald Campbell's proposal to buy 60 or 70 acres of additional Negroe Ground for Salt Spring, where he was now managing affairs for his father, had been approved by Duncan who was otherwise not inclined to the laying out of further money in Jamaica". (Note143)

Note 143: Duncan Campbell, letter to son Dugald, 6th January 1790.

Advice on the matter from William Brown, more experienced in the planting business and who supported Dugald's plan, tipped the balance in favour of a long term view on future economy. It was a view often reflected in announcements of estates for sale in which the extent and quality of provision grounds was prominent in the description; canny buyers would take note.

If field work was hard, the making of sugar and rum also tested endurance and were not without their own peculiar dangers, as Lady Nugent clearly details, and at length, after a visit to one sugar works.

24th February 1802.

After eating an abundant creole breakfast, set off for the sugar works. We then examined the whole process of sugar making, which indeed is very curious and entertaining.

The mill is turned by water, and the cane, being put in on one side, comes out in a moment in the other, quite like a dry pith, so rapidly is all the sweet juice expressed, passing between two cylinders, turning round contrary ways.

You then see the juice running through a great gutter, which conveys it to the boiling-house. There are always four negroes stuffing in the canes, while others are employed bringing in great bundles of them. Then, after the juice is expressed, the pithy stiff, which is called trash, is conveyed to a place below the boiling-house, to keep the fire going constantly.

In the boiling-house there are nine cauldrons; three of them merely simmer the sugar. This throws up all the scum and useless particles to the top of the cauldron. The pure liquor then runs into the first boiling cauldron, and is so conveyed to another, until it granulates. After that, it is carried by a large gutter into a large trough, called a cooler, from whence the negroes take it in pails-full, and put it into the hogs-heads, and so ends the process.

|

|

|

Strongbox as commonly |

Those casks, however, have holes bored at the bottom, and being on stands, the coarsest part, called molasses, runs through, and is used in the distilling of the rum.

Four negroes attend the mill, two put in the cane, one receives the dry cane, and throws it into the trash house, and there is always one attending to see that all is right and done well. At each cauldron in the boiling-house was a man, with a large skimmer upon a long pole, constantly stirring the sugar, and throwing it from one cauldron to another. The man at the last cauldron called continually to those below, attending the fire, to throw on more trash, etc; for if the heat relaxes in the least, all the sugar in the cauldron is spoiled. Then there were several negroes employed in putting the sugar into the hogsheads.

I asked the overseer how often his people were relieved. He said every 12 hours; but how dreadful to think of their standing 12 hours over a boiling cauldron, and doing the same thing; and he owned to me that sometimes they did fall asleep, and get their poor fingers into the mill; and he shewed me a hatchet, that was always ready to sever the whole limb, as the only means of saving the poor sufferer's life ...

After this, we went to the distillery, but this I cannot so well describe; but it seems that the molasses and dirty part of the sugar ferments, and, after passing through the fire and under water, in a long tube, it becomes a strong spirit. They have a sort of glass bead, by which they try the strength of the spirit, but I could not comprehend that part of it; and the smell of the dunder, as it is called, made me so sick, I could not stay to make a minute enquiry. (Note144)

Note 144: Maria Nugent Journal, 24 Feb. 1802

Upon such skill and labour depended the success of a crop. The value of a skilled elite to a proprietor, in the economy and smooth regulation of a plantation or a pen, might sometimes be recognised in cash terms, small amounts by any standard and certainly not wages, more reward or inducement:

Account Cash to Negroes

|

|

|

View of plantation, Knockalva, Jamaica. |

George at Argyle Pens, Cartmen, Drivers and trusty confidential Negroes paid, £2. 15. 0

William, Polidore, Peter, Isaac, Levant at Knockalva paid £1. 0. 0

George at Knockalva£1. 0. 0

Suckie at ditto £1. 0. 0

Hannah Snell at Argyle paid £3. 0. 0

To Barbara paid £5. 0. 0

To Molly paid £7.10. 0

To Dick, Johny, Fanny, Stella, Saray, Scipio, Peter, Lizy, Fortune, Philander, £3. 6. 8

For the Maintenance of the ten last negroes till provisions come in plenty paid, £5. 0. 0

To Robert Do., £2. 15. 0

To Tom Mullato Little Do., £2. 15. 0

£35. 1. 8, Barbery from McColl

£10. 0.0

£45.1.8

George Malcolm accounted for this "money to be given to Negroes" at Argyle and Knockalva (Note145) but whether such indulgence was also given at Richard Dickson's Cousins Cove or any other Hanover estate is impossible to say; given the familiarity between Malcolm and Dickson in particular (Note146) and among the resident planters in general, it is not wholly unlikely. Reward in the form of manumission did not necessarily have to wait upon an owner's death for it could serve the interests of both an astute master and an ambitious and literate servant, as Neill Malcolm intended in 1801.

Note 145: Cash Account, undated, in collection of early 19th C. Malcolm letters.

Note 146: Jamaica Almanacs: they were joint Lt. Colonels of the Hanover Foot Militia and also shared official parochial duties.

I have read B. Richard Brissets Memoranda. I consider him a well disposed negroe and might be useful by his advice and example to my estates. He now owes me a balance which I do not rightly recollect and ever since his return to Jamaica he has acted the same as if free without paying me any hire for such indulgence. However I take it for granted it would be my interest to accept of two good stout well disposed negroes in lieu of him and to give him his freedom agreeable to his Memorandum if he agrees to this on my return to London. I shall forward his manumission to be delivered to him on these conditions ... (Note147)

Note 147: Neill Malcolm to George and Donald Malcolm, 29 August 1801.

|

|

|

Abingdon great house, Jamaica |

Brissett had accompanied Malcolm to Scotland but had returned to Jamaica independently, presumably at Malcolm's direction. He was also clearly indebted to Malcolm, in a small way, but how he was expected to find money for the two slaves which were to be the price of his freedom is, unfortunately, not revealed. Malcolm perhaps implied that Brissett, by acting the same as if free, was engaged in some business on his own account and could therefore be expected to arrange the necessary purchase price in exchange for his papers.

As to the general care and control of plantation slaves, this varied as much as the individual disposition of the owners and their employees themselves. On the one hand the diaries of Thomas Thistlewood, of Westmoreland parish, reveal him as a much disturbed and alarming man with equally disturbing and vindictive tendencies. On the other hand Simon Taylor was quite categorical when he wrote to Chaloner Arcedeckne, in 1788 (Note148), that as for Cruelty there is no such thing practised on Estates....

Note 148: Institute of Commonwealth Studies: Simon Taylor letters, Taylor to Arcedeckne, 29 May 1788.

His comment was a reaction to tales of cruelty current in Britain at the time and he went on to assert that if they were true the slaves would have cutt all our throats allready. Taylor's statement was, perhaps, somewhat disingenuous but he was right to raise the subject of slave welfare which, for owners such as himself, was as much the practice of sound economics as well as a matter of humanity. By habit they were certainly proprietorial but also pragmatic, a view best summarised by Duncan Campbell in a letter to his son Dugald at Salt Spring in 1790:

...I am glad to observe you are making the necessary exertions for succeeding Crops ... The quantity you expect this year I hope may be increased without overworking your Negroes, which is at all times to be avoided, as well from motives of humanity, as real benefit to our Interests. (Note149)

Note 149: Duncan Campbell, letter to Dugald Campbell, 3rd February, 1790.

(Ends Part Two of Kin and Creole, Jamaica by Peter Dickson)

Other sections of Peter Dickson's article appear

at: |

This free script provided by

JavaScript Kit

View web stats from www.statcounter.com/ for this website begun 4 July 2006